A short history of gender neutral jewellery

… purse by Hopetown and Hunter

Throughout the whole of human history, wealthy men and women (even those with more moderate incomes), have claimed social status through the wearing of semi-precious and precious stones, gold, silver and bronze. But jewellery has never been just about rank. Jewellery, self-adornment, have always been about self-expression. Even before the emergence of modern man, human primates loved to adorn their bodies with decorative objects.

Pre-modern Man

Neanderthals are not generally associated with handicraft, but according to Archaeologist João Zilhão, not only did Neanderthal man, or woman, fashion jewellery from shells but they also added a glitter-like substance to their jewellery to give it an added lustre. Zilhão argues the significance of the need to self-decorate in this way as evidence of ‘symbolic thinking.’

Zilhão explains symbolic thinking as…

"Something that people wear in order to convey what they are… And you only need to do that in a world where you have a complex network of relations, because if you only interact with your family, or people you've known all your life, they know who you are, you don't need to use an identity card."

Eagles talons with marks showing how they might have been strung together. Approx 130,000 years old

‘Glitter’ added to Neanderthal shell decoration

Unisex Jewellery

From the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries there has been an escalation of interest in examining, and blurring, the boundaries of masculine and feminine fashion and jewellery, but we are not the first to embrace the wearing of non-gender specific ornament.

The remains (dating back to the mid-5thcentury) of a high-ranking adult male, were found in a grave at Varna (modern Bulgaria). His body is sprinkled inh gold necklaces, bangles and rings, his skull surrounded by golden shell-like objects, the piercings on which suggest they were once strung together to form a headdress or necklace.

We cannot know for sure that female members of his tribe wore equivalent decoration, but we do know that jewellery was buried with a body as means of protection from malevolent spirits and as a way of ensuring safe passage into the next world. It would be reasonable to assume that these treasures, designed for good outcomes in the afterlife, were also granted to high-status female members of the tribe.

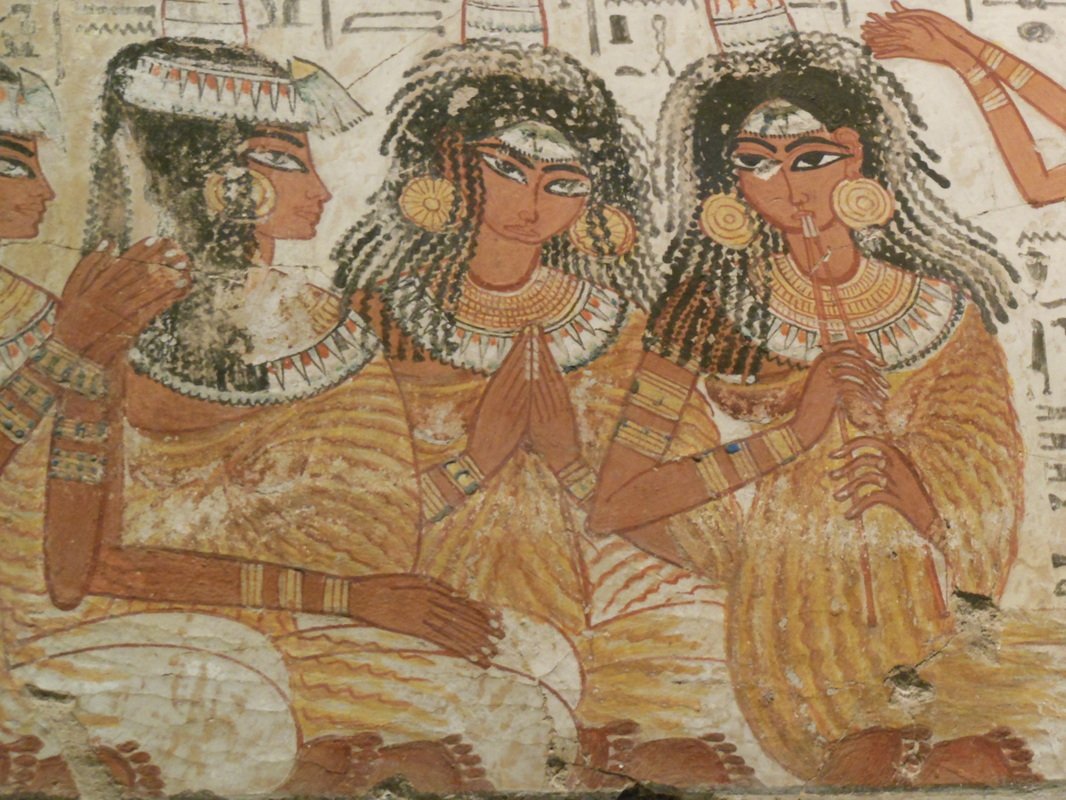

Ancient Egyptians

We know from the plundered tombs of the Pharaohs that Ancient Egyptian jewellery was gender- neutral. Both sexes wore neck collars, bangles, bead necklaces, earrings, and rings. The theory that ‘Golden fly’ pendants were given as decorations for bravery, or success, in battle, has been discredited by evidence that these objects were found in the graves of women and children, as well as men.

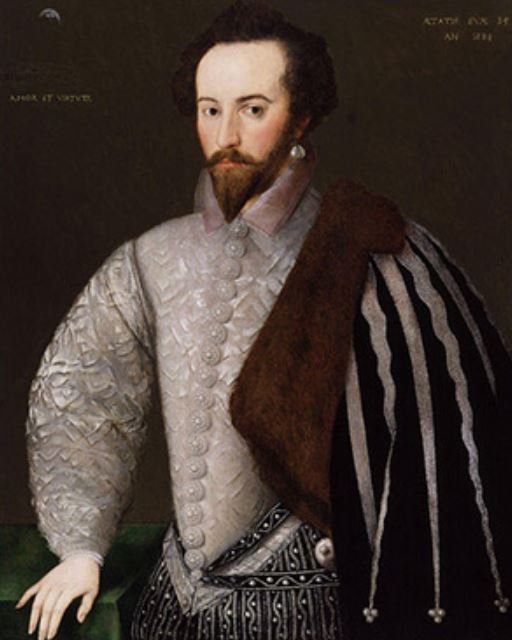

The Elizabethans

During this period, women and men wore the same types of jewellery: ornate chains, brooches, girdles, decorative collars, circlets, earrings, and chaplets. In a time when the national ruler was female, it’s possible to see how jewellery might achieve gender equivalence.

The Victorians

The Victorians idealised their mothers and daughters. The ‘Angel in the House’ was pliant, loving and raised legions of children for the service of Queen and Empire. The gender divide had never been sharper, the roles of men and women distinct and immovable.

Gender neutral jewellery at this time was practically non-existent, the only acceptable adornments for men were functional: pocket watches and signet rings. Women wore delicate lockets, pretty bracelets, and cameos in the likeness of beloved family members.

The Sixties

It was not until the Sixties and the emergence of youth culture that the divide between masculinity and femininity began to break down and jewellery became less about gender identity and more about an exploration and expression of self.

Aldo Cupillo and the iconic Juste un Clou Bracelet

When Aldo Cupillo moved from Tiffany to Cartier in the late 1960s, he brought with him a much- needed injection of youth culture and movie star glamour. His still popular Love Bangle, worn by men and women alike, was a re-imagining of the chastity belt and came complete with mini padlock.

Inspired, it is said, by the nails used at the Crucifixion, and his own sense of the central importance of nails in everyday life, Cupillo created the Juste un Clou (just a nail) bracelet. The clean, shatteringly bold design made the Juste un Clou bracelet one of Cartier’s iconic designs. It is still popular with both sexes today.

Seventies

The seventies brought Flower Power and Glam Rock and a playfulness in both fashion and jewellery that set the stage for a growing interest in gender-neutral adornment and continued the social revolution, begun in the Sixties, against the gender codes and straitlaced social norms of the first half of the twentieth century.

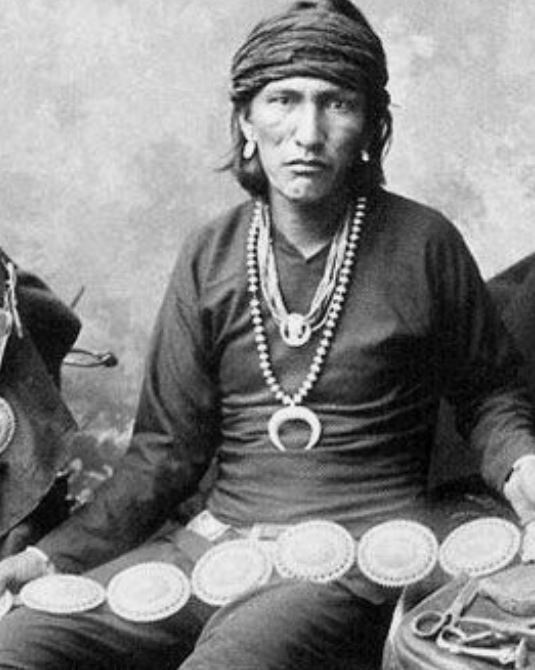

First Nation Peoples

In less fractured societies than our own, where hierarchy, gender roles and a fixed social structure have endured for hundreds of years, it’s possible to read the prevalence of gender-neutral jewellery as a signifier of gender equality. The roles of men and women may be different but are of equal importance and value.

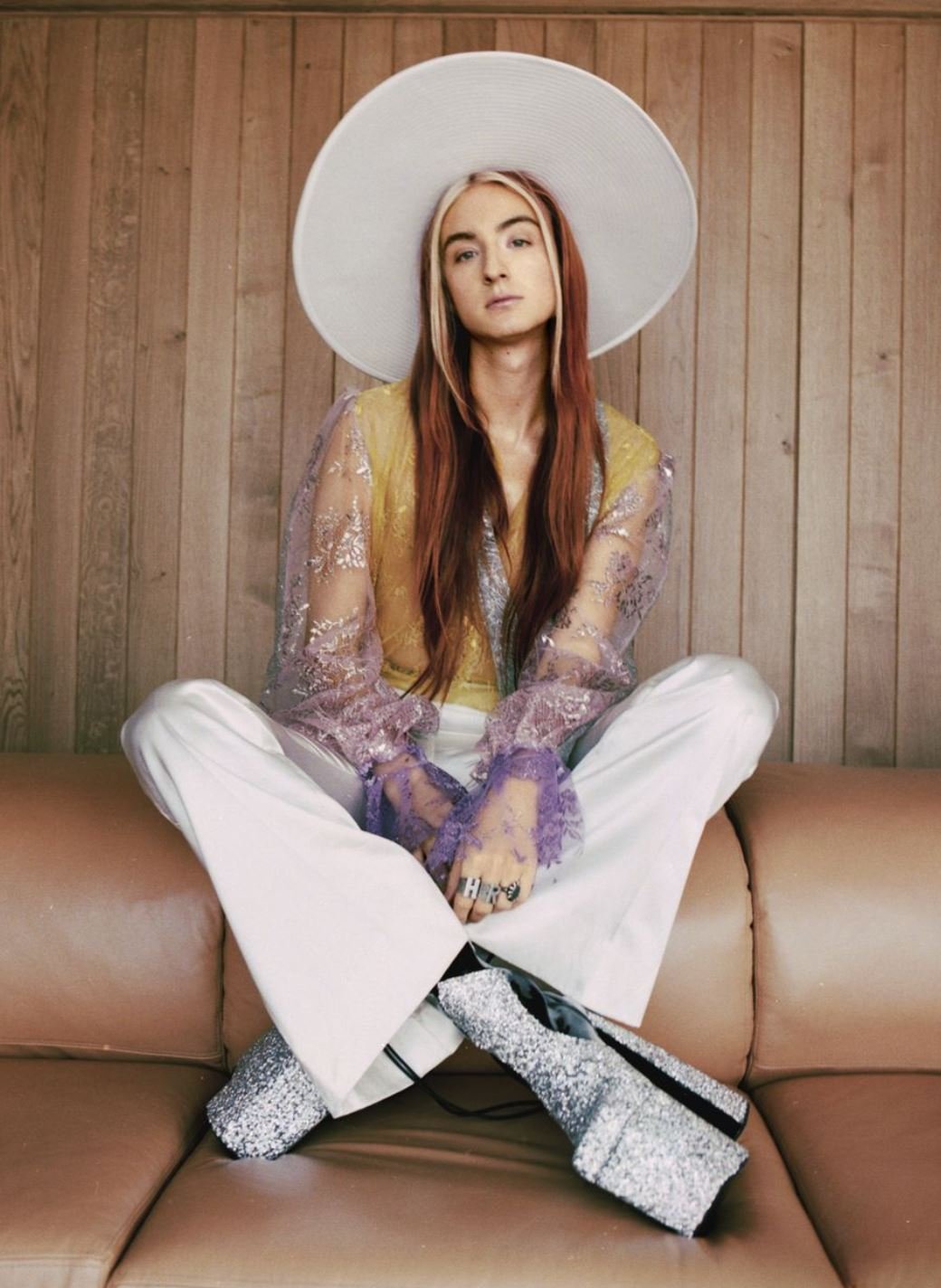

21st Century and beyond

As conversations around gender identity become ubiquitous, there may come a time when gendered jewellery becomes a thing of the past, when all sexes can use the same jewellery as expression of self, for personal adornment, and to have fun.

References and Further Readings

https://the-past.com/feature/golden-flies-as-military-awards-it-doesnt-fly/

https://www.lbma.org.uk/wonders-of-gold/items/snettisham-hoard-great-torc

https://womenofegyptmag.com/2019/05/20/11-pieces-of-jewelry-from-ancient-egypt/

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/10/books/review/empress-nur-jahan-ruby-lal.html

https://www.harrisreed.com/about

https://www.byrdie.com/mens-unisex-jewelry-brands-7099458

https://www.nonamemakings.com/multi-configurable-unisex-jewellery

https://mateonewyork.com/collections/necklaces

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/jan/13/neanderthal-man-archaelogical-research